Homosexual couples have been out and proud in Switzerland for some time now. Same sex love is widely accepted by society. Nevertheless, gays and lesbians repeatedly experience hostility and even violent attacks. For example, the media reported a case where a homosexual couple were beaten up by a group of young men and called “faggots” and “freaks” late at night in the middle of Zurich. By its own account, the organisation Pink Cross receives up to four reports of homophobic attacks per week. There are no statistics about crimes on the basis of the victims’ sexual orientation in Switzerland. Furthermore, many attacks go unreported because the victims decide not to go to the police.

Collective violations of personal honour are no grounds for legal action

Anyone who sows hate against homosexuals can only receive a suspended sentence. Any person who personally suffers verbal abuse can lodge a complaint on the grounds of defamation or slander. However, the violation of personal honour article in criminal law does not apply if an entire group, such as homosexuals or lesbians, is affected by verbal abuse. For this reason, a local Appenzeller politician of the extreme-right PNOS (Swiss Nationalist Party) was able to label homosexuals as “demographic deserters”, insinuate that they are capable of “doing pioneer work for paedophiles”, and propagate the “Russian solution” (in Russia, homosexuals and lesbians are subjected to reprisals) with impunity on Facebook. A collective criminal complaint by Pink Cross for violation of personal honour was unsuccessful. The public prosecutor halted the legal proceedings as there was no legal basis.

Valais SP National Councillor Mathias Reynard would like to close this loophole in criminal law by extending the anti-racism provision to include sexual orientation. “Homophobia is not an expression of opinion and should be recognised as an offence just like racism or anti-Semitism,” argues Reynard. The anti-racism provision, which protects people from verbal abuse on the grounds of their race, ethnicity or religion, has been in force since 1995. In 2013, Reynard started a parliamentary initiative with the demand to extend discrimination protection to the category of “sexual orientation”. The national councillor received strong support from his colleagues for doing so. The National Council even wanted to take it further and include the criterion of “sexual identity” in the provision to protect homosexuals and lesbians as well as bisexuals and transgender people (LGBT) from hate crime. However, that was a step too far for the Council of States. It said “sexual identity” was not clearly tangible, which could lead to interpretation issues. Finally, the two chambers agreed on an extension of the anti-racism provision to include “sexual orientation”.

Christian-conservative opposition to “censure law”

Liberal judges in Parliament were fundamentally sceptical about additional bans on discrimination. Appenzell FDP Federal Councillor Andrea Caroni pointed out that criminal law is “too big a stick” for such cases. He invoked freedom of expression and warned against criminalising discrimination on the grounds of language, nationality or sex. “It will never end”. The “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” also warned against new bans in a commentary, and called for people to stop homophobes with civil courage and clear language.

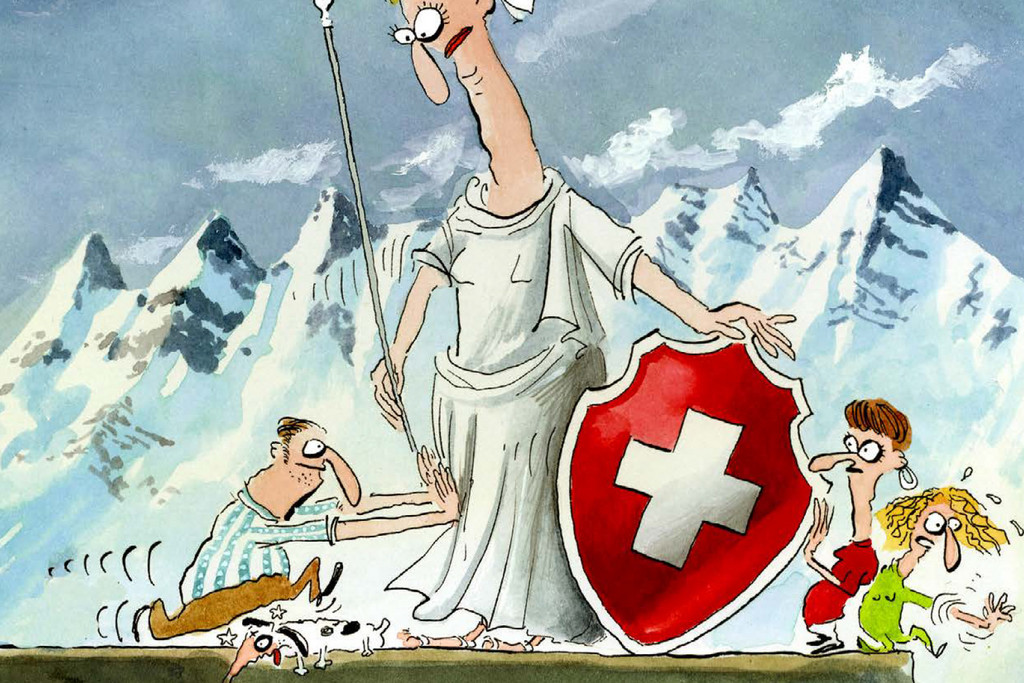

There has been fundamental opposition to the extension of the anti-racism provision to homosexuals and lesbians from the Christian Conservative Party EDU, the Young SVP and the Youth and Family working group. A joint committee collected 67,500 valid signatures for a referendum entitled “No to the Censure Law”. So, the submission will now be put to the voters for a decision on 9 February 2020.

Opponents criticise what they see as a disproportionate restriction on freedom of conscience. EDU President Hans Moser fears that pastors will attract the attention of the justice system in the future “when they cite biblical truths”. For many free churches, same-sex love is incompatible with a life according to the tenets of the Bible. Critical public examination of homosexuality must remain a “legitimate position”, writes the committee. Opinions must not be criminalised and there is the danger of “perspective justice”. The Young SVP want to prevent “freedom of expression from being restricted even further”. In doing so, the party is basically focusing on the anti-racism provision, whose abolition they are once more calling for.

Judges place great importance on freedom of expression

Twenty-five years before the introduction of the anti-racism provision, opponents focused on freedom of expression during their campaign against the “muzzle law”. In the referendum in autumn 1994, around 55 per cent of voters accepted the submission. This cleared the way for Switzerland to enter the UN Convention as the 130th state to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination.

The question of whether you “can no longer say everything” has come up time and again since then. Is freedom of expression in Switzerland actually in danger? Judge Vera Leimgruber has analysed the previous legal judgements on the anti-racism provision on behalf of the Federal Committee against Racism (FCR). In the process, she came to the conclusion that the article has been used very sparingly to date, and that judges have placed great importance on the argument of freedom of expression in borderline cases. However, statements which belittle human dignity are not borderline cases. Human dignity is at the heart of basic human rights.

Accordingly, the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland convicted two SVP officials of publishing an advertisement with the title “Kosovars slash a Swiss”. During the campaign ahead of a vote on the mass immigration initiative the party brought up the case of a criminal of Kosovan origin who attacked a Swiss citizen with a knife in Interlaken. The Federal Tribunal concluded that with the “sweeping judgement” in the advertisement, Kosovars had been denigrated as an ethnicity and portrayed as being inferior. In doing so, the party had also created a climate of hate.

jazumschutz.ch

www.zensurgesetz-nein.ch

www.ekr.admin.ch

Comments