The book covers 700 pages and contains 453 different entries – from Alpenbitter to Zigerkrapfen. There is a lot of material. Can the author name one of his favourite items? How about Chèvre? “A real discovery,” Imhof calls it. Chèvre is a sparkling digestif from French-speaking Switzerland that dates back three generations or more. A handful of vignerons in Geneva still produce it at harvest time. Imhof visited one such grower, where he learned how rice flour, grape sugar, eau de vie, and vanilla pods are added to grape juice that has started to ferment.

The blend continues to ferment for at least a month in a barrel reinforced with steel hoops. “The vessel would explode otherwise.” This produces a sparkling beverage that is ready to drink by New Year’s Eve. Fresh on tap, the white liquid shoots out almost like milk from a goat’s udder. Chèvre is French for goat. Another of Imhof’s discoveries is Furmagin da Cion from Val Poschiavo, a valley in the Italianspeaking part of the canton of Grisons. Cion means pig in the local dialect, while the name Furmagin derives from a type of cheese called Formaggetta.

But Furmagin da Cion is not a dairy product but a meat speciality. Every local family traditionally used to make their own Furmagin during pig slaughtering, using the inferior cuts and the offal. They would bake it in the oven like a cake. Nose-to-tail eating is now a trend but was par for the course back then. Butchers in Poschiavo still produce Furmagin to this day – and have refined their recipes. Imhof: “What used to be a type of food eaten by the poor has become a popular speciality.”

Investigating and documenting

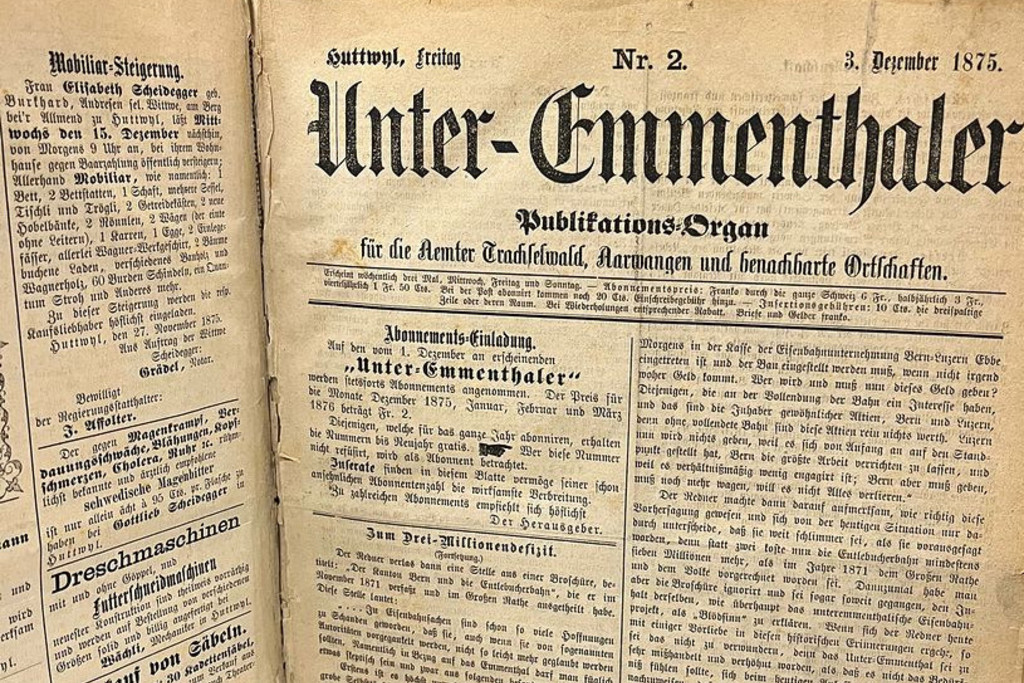

Why study Switzerland’s culinary heritage? And how? The Vaud National Councillor Josef Zisyadis got the ball rolling 25 years ago. “Zisyadis submitted a motion to prevent Switzerland’s culinary traditions and knowledge from being forgotten,” Imhof explains. The Federal Council and parliament approved the motion, and a team of experts commissioned by the government and the cantons started work. They scoured libraries and archives, spoke to producers and built up a catalogue of products, preparation methods, and recipes. The results of their investigative work were published online at www.patrimoineculinaire.ch in 2008.

Imhof, now 72, was involved from the outset. The journalist took it upon himself to produce a readable guide book based on this detailed online inventory. Five volumes were published in 2016, some of which sold out. His latest work is an updated, complete edition. It covers new items that have since met the requirement of having been available for at least 40 years. Ticino rice is one example – thanks to climate change, the author notes.

Imhof’s writing is humorous and rich in information. The author supplements his entries with historical facts and lively anecdotes that he has researched himself. Structured by canton, his book takes the reader on an educational journey through Switzerland’s diverse culinary heritage, where myriad domestic and outside influences intersect. There is no such thing as a Swiss national dish, he says. “Switzerland’s culinary wealth is regional in character.”

The role of the land

Nevertheless, the undulating nature of Switzerland’s own patchwork landscape was a key influence in itself. Arable land used to be scarce before many of the country’s waterways were artificially straightened. According to Imhof, widespread livestock farming meant that the Swiss were masters at preserving food. Milk was preserved as cheese, and meat was turned into sausages or dried into ham – building up provisions that could be sold immediately. Sbrinz, “the oldest Swiss cheese export”, was transported across the Alps to the markets of northern Italy. Schabziger herbal cheese from the canton of Glarus found its way to the markets of Zurich. “A land or country always defines itself by what it eats,” says Imhof.

Switzerland’s rich culinary heritage is born of resourcefulness, he continues. Commercial products like Aromat, the famous yellow powdered seasoning, or Rivella, the quintessentially Swiss fizzy drink derived from whey, are as much a part of our repertoire as Birchermüesli and grandma’s lebkuchen recipes. In this age of ready-made meals, additives, and social media food porn, Imhof believes that a return to the tried and trusted is more important than ever. The book is also a eulogy to the original guardians of good taste – “the farmers, the maids and the cooks”. And to the creativity of butchers who through the centuries came up with over 400 types of sausage, of which only a fraction appear in the book. Such traditional products continue to underpin the work of all artisans, he adds. Incidentally, Imhof claims that the canton of Solothurn is the spiritual home of Switzerland’s favourite sausage, the Cervelat – not because the smoked speciality was invented there, but because of Olten, one of Switzerland’s most important rail hubs. The hearty Cervelat-based salad (Wurstsalat) served at Olten’s famous station restaurant made a name for itself well into the 1980s.

Glacier wine

The book’s Vin du glacier entry provides an insight into the old nomadic, transhumance lifestyle of people who moved between the high pastures and the valleys of Valais. Farmers in the 18th century grew vines in the former marshlands of the Rhône Valley. After pressing the grapes, they would transport the wine up to the highmountain villages, such as Grimentz below the Moiry Glacier. Each family made enough wine for themselves, and then a little extra.

This went into an old larch barrel, kept to one side in a cold, dark cellar, and never emptied. The barrel was topped up every spring. Some of these vessels are now very old and are treasured family heirlooms. “In 2022, the oldest barrel, dating back to 1886, contained wine from 130 different vintages,” says Imhof, who can report first hand that glacier wine tastes a bit like sherry.

Imhof himself was a Swiss Abroad in the 1980s and 1990s, reporting for the “Basler Zeitung” as a journalist in south-east Asia. He observed how Swiss chefs at hotels in Singapore liked to cook with local produce but had things like cream and chocolate delivered to them. “Swiss Abroad have also done their bit to preserve our culinary heritage.”

One last question for the author. When Swiss expat clubs meet around the world, they invariably eat fondue together. Shouldn’t that be our national dish? When push comes to shove, yes, fondue, he replies. If Switzerland is synonymous with one thing, it’s cheese.

Comments