All parties must be prepared to give and take – this was the spirit embodied by the “Old-Age Pension 2020” project. What some people saw as good old-fashioned Swiss compromise was regarded as a fiasco by others. Greater revenues and savings were to balance the books of old-age and survivors’ insurance (AHV) until 2030. The conversion rate was to be lowered to stabilise occupational pension provision, in other words the pension funds. It was hoped that the level of old-age pensions could be maintained thanks to restructuring of the pension funds and a 70 Swiss francs a month rise for the new AHV pension. The pension age for women was to gradually be brought into line with that for men, so from 64 to 65 years of age. It also intended to make retirement more flexible between the ages of 62 and 70.

Seven years were spent tweaking this bill only for voters to scupper the entire reform package on 24 September 2017. In total 52.7 % were opposed to the Federal Act on Pension Reform. The additional funding of AHV through an increase in VAT was also rejected by 50.05 % of voters and the majority of the cantons. After a 20-year reform backlog on old-age pension provision, the SP Federal Councillor Alain Berset had wanted to reform and stabilise both the first pillar – AHV – and the second pillar – the pension funds – with a comprehensive package.

Berset’s mammoth undertaking

The wide-ranging scope of the proposal had benefits but also the drawback of being extremely complex. It also provided angles of attack for all sides. Both the conservatives and the left-wing parties were divided amongst themselves. The FDP and SVP joined forces to oppose the bill. The 70 franc increase was their main bone of contention. The Federal Council, a small parliamentary majority, the SP and CVP did their utmost to get the reform bill through. However, in French-speaking Switzerland it was far-left groups who successfully called the referendum. They saw the increase in the pension age for women as socially unacceptable.

Interior Minister Alain Berset conducted a highly committed referendum campaign, making numerous appearances throughout the country, and did not hold back from making dramatic statements. He warned young people that they risked not receiving AHV in future if they rejected the bill. These and similar remarks were construed as counter-productive threats by various sides.

SVP and FDP team up with the far left

The two major right-wing parties – the FDP and SVP – were thus able to defeat the reform package in an alliance with the far left. In large swathes of French-speaking Switzerland the rejection of the reform can therefore be interpreted as a no from the left. But contrastingly it was the right who said no in German-speaking Switzerland. Both sides are now fighting for sovereignty over the interpretation of the result in the aftermath of the battle.

However, a wide variety of factors contributed to the failure of the pension reform. This makes the search for a quick and viable solution difficult. Stabilising the social institutions is imperative in view of increasing life expectancy and the ageing of society. Federal government calculations indicate that the AHV system will face a shortfall of seven billion Swiss francs by 2030. Federal Councillor Berset will now get all the parties and associations together around the table as a first step. The conservative opponents of the reform were already alluding to a plan B prior to the referendum. SVP President Albert Rösti said on Swiss television on the Sunday of the referendum that a broad compromise would have been reached in Parliament had the 70 franc increase in AHV not suddenly been added. FDP President Petra Gössi outlined her plan B as follows: the pension age for women would rise to 65 years of age, VAT would also have to be increased for AHV and the pension age would be made more flexible. The main reason for the rejection of the bill, she said, was the 70 franc increase in AHV: “A rise in AHV must therefore be definitively ruled out. The majority of Swiss people do not support this supplement,” she said. The conservatives also want to reform the first and second pillars in separate bills.

The red lines

For his part, SP President Christian Levrat made clear on referendum day where the red lines were for his party: “No reduction in pension, no increase in the pension age for women to 65 without compensation and no general increase of the pension age to 67.” The supporters of the bill did not regard the infamous 70 francs as a pension rise, as opponents complained, but rather as a form of compensation. CVP President Gerhard Pfister also remarked that the pension age could not be increased without compensatory measures.

It was not by chance that Levrat warned of a pension age of 67. The issue was not up for discussion as part of the defeated bill but it was nevertheless raised by SVP President Rösti on the evening of the referendum. Hans-Ulrich Bigler, FDP National Councillor and Director of the Swiss Trade Association, mentioned a “moderate increase in the pension age in monthly increments” shortly after the referendum. The “Neue Zürcher Zeitung”, the mouthpiece of conservative Switzerland, maintained: “Debate over a higher pension age is now urgently needed after the referendum.” In contrast, “Der Bund” commented: “Some people on the right and business leaders hope the people are willing to accept a pension age of 67 as they areunder the impression that the AHV system is facing a financial crisis. This is a cynical and dangerous calculation. A general increase in the pension age will not gain majority support in the foreseeable future.”

The row over a new pension bill is already raging between politicians and in the media. The search for consensus will prove difficult, especially since the conservative victors of the referendum on 24 September cannot put forward a bill without reaching agreement with the left if another debacle at the ballot box is to be avoided. After all, a referendum on AHV has never been won without the support of the left.

Yes to food security

Overshadowed by the referendum on old-age pension reform, the issue of “food security” was also decided at the ballot box – this concerned a counterproposal to the popular initiative of the same name put forward by the Swiss Farmers Union. Not opposed by any of the parties, the bill was also approved by the Swiss people with 78.7 % voting in favour. However, the new legal norm will not change anything as no legislative amendment is provided for. “The new constitutional article supports the general thrust of current agricultural policy,” according to the Federal Council’s official explanatory statements. The constitutional article lays down how food supply for the population is to be secured on a long-term basis. These are matters which were essentially already covered by the Constitution but are now enshrined as a comprehensive concept, including securing the basis of production, especially arable land, resource-efficient food production adapted to the location and a market-oriented agricultural and food industry. The new article leaves scope for very different interpretations. Farmers may see it as a requirement for greater structure, and environmental associations as a remit for a more eco-friendly approach.

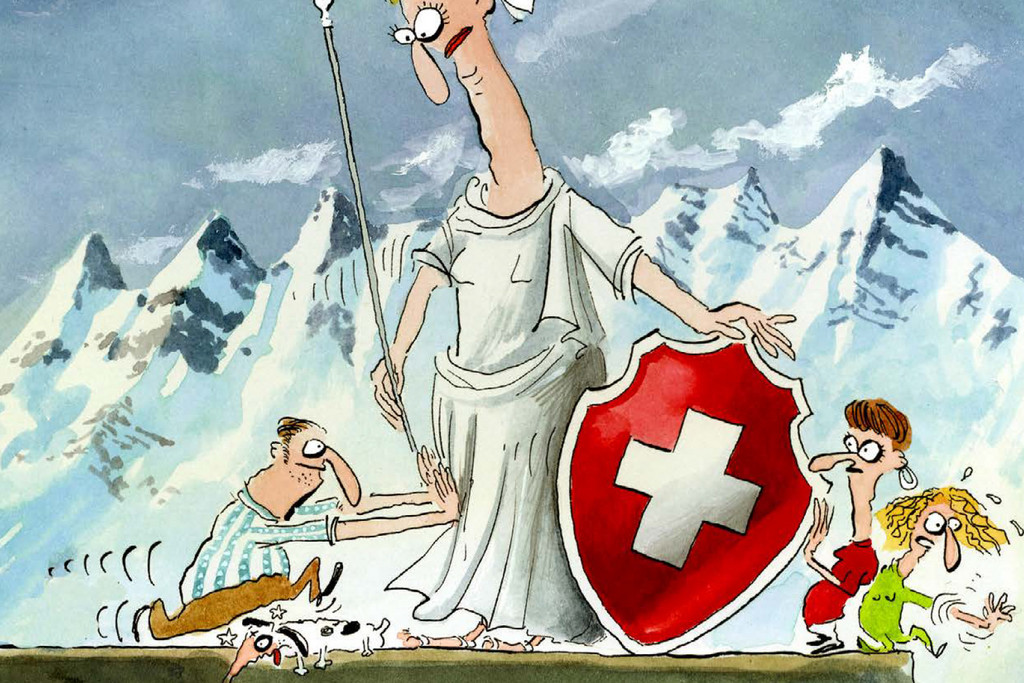

Picture The opponents of the pension reform bill triumphed with their arguments. But what now? Photo: Keystone

Comments