After the first decisions made in 2015 – the elections to the cantonal parliaments of Basel-Land and Lucerne – conjecture that a factional election campaign will be carried out at the federal elections in the autumn has been confirmed: the conservatives against the rest. The centre is likely to fall by the wayside, as are the Greens and the left. In addition to the above-mentioned, this should also be a cause of concern for the BDP – which broke away from the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and whose full title is the Conservative Democratic Party – as well as the Green Liberal Party (GLP).

But what does “conservative” actually mean? And what does “centre-left” signify? This battle cry and term of differentiation is used by the right primarily to qualify the current Federal Council, along with Federal Councillor Widmer-Schlumpf who was ostracised from the SVP, as inadequate.

Four members of the current Federal Council belong to the conservative alliance made up of the Radical Free Democratic Party (FDP), the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and the Swiss Christian Democratic People’s Party (CVP). To define Evelyn Widmer-Schlumpf as left-wing is impossible under the conventional criteria of political analysis. The two Social Democrats are faced with a solid non-social-democratic majority. The Federal Council accomplished the 2012/2015 legislative term very successfully. However, the leaders of the conservative parties declare that this dangerous centre-left alliance should be voted out of office.

The current election campaign rhetoric and the reality of Swiss politics to date are not really congruent. How can this be explained? And what does this explanation say about the (effective) Swiss way of government? Neither these questions nor the answers are particularly original, but they are nonetheless not redundant. They give an indication of the reality of Switzerland’s public media which have also undergone transformation. It is a reality that no longer readily tallies with the long-established hallmark of Switzerland as a political nation with its steadfast common sense.

Why adopt a “factional election campaign” approach as a method in the quest for votes? Quite simply because it concurs best with the logic of modern-day media campaigns. The objective is simplification including the associated identification of the enemy. “Us against them” is the ethos. This reduces uncertainty and provides assurance of being on the right side.

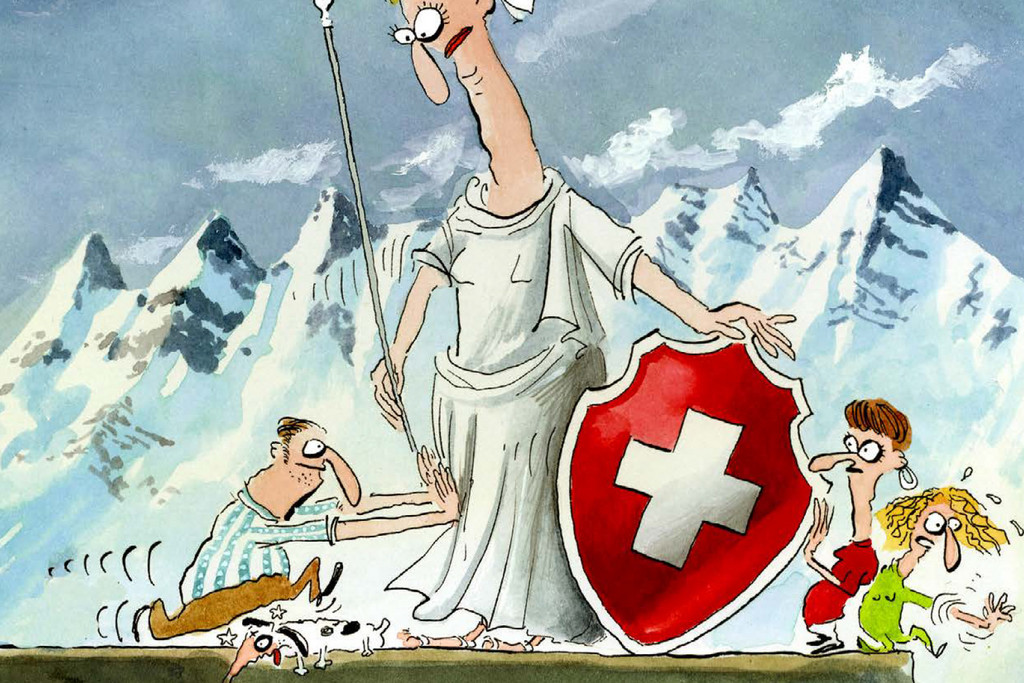

The technique is as old as the laws of political power. It has been deployed by both left and right, by Lenin as well as Goebbels – and by many victory-oriented election campaigners in democratic countries. But does it fit in with Switzerland’s special form of democracy? Absolutely not in actual fact. This is because the Swiss constitution and the problem-solving processes contingent upon it are structurally geared towards compromise, integration and conciliatory, inclusive results which take account of all interest groups as far as possible.

To sum it up in a contrasting pair of notions, they are calibrated towards “conservative” agreements in the sense of republican public-spiritedness and not primarily focused on the “conservative” system in the sense of minimal-state economic freedom.

The reigning Federal Council that is democratically elected by a democratically elected Parliament only appears centre-left because it has conformed with the conservative-republican constitutional consensus over the past four years and by no means without success. It is only “un-conservative” to those who associate conservatism with everything that concurs with the either-or systems of UK-style, majority-based parliamentary democracy but not with Switzerland and its idiosyncratic concordance-oriented democracy which has developed over the course of history.

To reiterate the point, the Swiss system has encompassed – for many years and for good reason – the broad bearing of power, respect for differing opinions and the recognition in principle of the legitimate co-determination of the common res publica by the opposition.

One might contend that the modern electoral campaign now has its own laws. While that might be true, it does not alter the fact that this is not good for perhaps the best aspect of Swiss political culture, its common sense.

Comments

Comments :