Smoking among the young: Switzerland lags behind

24.03.2023 – STÉPHANE HERZOG

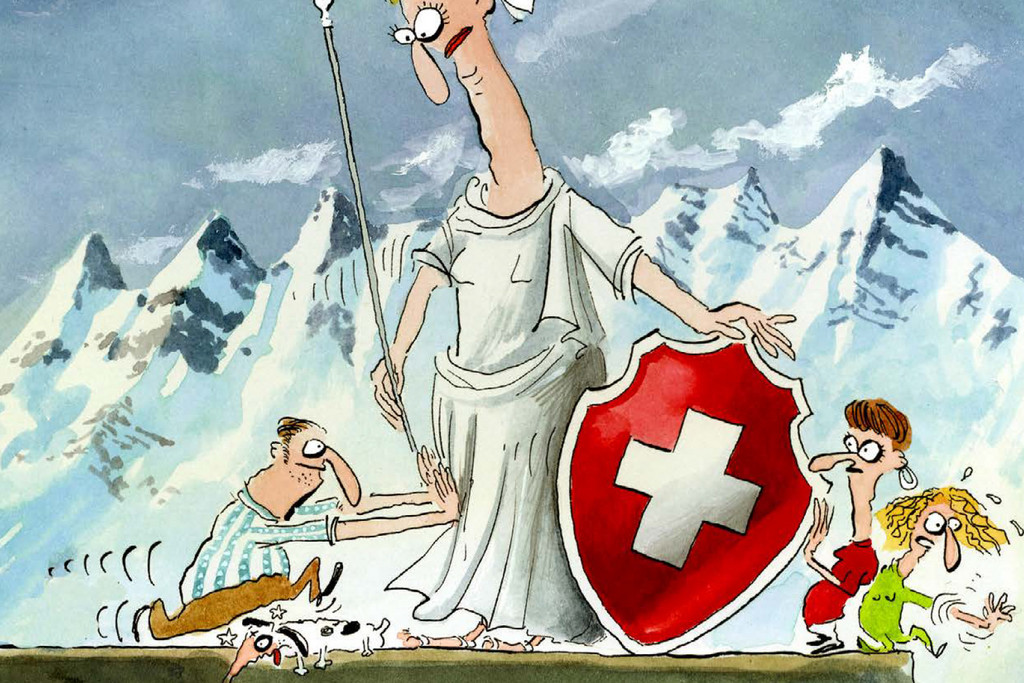

Switzerland is currently at the bottom of the European ranking in the fight against smoking. An initiative banning advertising aimed at minors was approved in 2022. Prevention is now facing off against the might of Big Tobacco.

“This is a significant improvement.” Camille Robert, co-director of the “Groupement romand d’études des addictions” (GREA) network, recalls her sense of satisfaction when the popular initiative “Yes to protecting children and young adults from tobacco advertising” was accepted in February 2022. This constitutional article should come into force in 2024. The Federal Council has announced that “it will result in an almost total ban on advertising, since there are few places or media which minors cannot access”. These provisions will be incorporated into the tobacco products act.

Launched in 2015, it aims to regulate a wide variety of products, all of which serve to deliver nicotine to consumers, e.g. cigarettes, heated tobacco, e-cigarettes, tobacco placed between the gums (snuff/snus), nicotine substitutes.

Despite this progress, prevention groups remain wary. “Whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a total ban on advertising, Swiss law stipulates a list of certain bans on advertising and sponsorship, which will leave space for the tobacco companies,” comments Vanessa Prince, project manager at Unisanté (VD). Pascal Diethelm, president of the OxySuisse association, also sees a major flaw. “By focusing attention on the under-18 group, this law risks reinforcing tobacco’s appeal among young people as forbidden fruit”. As an example, he refers to a booth set up at the last Montreux Festival by British American Tobacco, reserved solely for adults. “It’s exclusive, and that attracts young people,” he adds. Such messages normalising tobacco use can be found on social networks. “Smoking is a juvenile disease that is being transmitted through social networks on a wide scale,” states Swiss physician Reto Auer, who works with Unisanté. According to prevention associations, the best way to protect young people from tobacco would be to ban advertising completely, as recommended by the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Although Switzerland signed the convention in 2004, its ratification is not on the agenda at the moment.

An empire of multinational tobacco companies

The might of the tobacco industry in Switzerland is contributing to this reticence. The country is home to Philip Morris (PMI), Japan Tobacco International and British American Tobacco Switzerland. PMI alone manufactures over 20 billion cigarettes a year in Neuchâtel, including small cigarettes for its IQOS heated tobacco device. “The tobacco industry has managed to form alliances with the economy and the most conservative parties,” Diethelm explains. An SVP national councillor – Raymond Clottu (NE) – declared in 2016, for example, that “cigarette advertising is not intended to encourage smoking, it’s simply an instrument of legitimate competition between markets”.

Ultimately, Switzerland was ranked 35th in the Tobacco Control Scale 2021 in Europe, second-to-last before Bosnia-Herzegovina. Its score was 35 points, compared with 82 for Ireland, which received good marks in eight areas, including increased prices for a packet of cigarettes and measures to ban smoking in public spaces. With regard to advertising, countries such as Finland and Norway, which have a complete ban on advertising, were awarded the maximum number of points (13), while Switzerland received two points. “In some countries, cigarette packs are very plain and not even visible at the point of sale, which lessens marketing appeal,” says the president of OxySuisse. What effects will the impending law on tobacco products have on this aspect of prevention? “Switzerland could achieve around ten points, but not the maximum because there will still be forms of advertising permitted for those over 18,” acknowledges Jean-Paul Humair, medical director of the Centre for Information and Prevention of Tobacco Use in Geneva.

“Whereas the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a total ban on advertising, Swiss law stipulates a list of certain bans on advertising and sponsorship, which will leave space for the tobacco companies.”

Vanessa Prince

Project manager at Unisanté

Limited prevention

Prevention organisations are looking for a law that goes further. In particular, they deplore the fact that Switzerland has only one global health survey, carried out just once every five years. The prevalence of smoking – and vaping – among young people should, however, be monitored much more closely. In a survey of upper secondary school students in 2020 and 2021, 12 percent of 15-18-year-olds said they smoked every day and 2 percent vaped daily. Although age comparisons with other countries are complicated, overall the fact remains that 27 percent of the Swiss population smokes, compared with about 15 percent in Australia, where the battle against tobacco use is very aggressive.

…and cheap packet prices

Another prevention tool is to increase the price per cigarette pack, which leads to an equivalent reduction in consumption by young people, states Humair. According to the latest report by the Federal Commission for Issues relating to Addiction and the Prevention of Non-communicable Diseases, the price of cigarettes is abnormally low in Switzerland compared with other countries. A packet costs CHF 9 in Switzerland as against CHF 15 in Ireland. Each pack sold generates CHF 4.60 for the OASI pension fund, 2.6 centimes for the Tobacco Control Fund and the same amount for the fund promoting tobacco cultivation. “The tax charged for OASI poses a problem of social justice, because it forces people to contribute even though not all will benefit from it due to diseases caused by tobacco,” explains Camille Robert. This issue is not covered by the bill.

Nicotine debate undermining prevention

GREA also believes that anti-smoking campaigns are under-resourced. “They have little impact on young people in general. Actions aimed at supply and demand or helping young people understand the mechanisms used in advertising are more effective,” comments Jean-Paul Humair. Unisanté accomplishes this with a tablet app that encourages teenagers to discover advertising messages hidden in images presented in the form of an Instagram feed.

The debate on cigarettes is intertwined with a second debate concerning access to nicotine. And this issue divides prevention professionals into two camps. The Swiss Association for Tobacco Control advocates a “tobacco-free and nicotine-free” Switzerland. Other health professionals view e-cigarettes – containing nicotine – as a risk reduction tool. They point to the fact that it is tobacco, not nicotine, that kills more than 9,000 people every year. The problem, however, is that these conflicting messages end up muddying the prevention waters.

Comments

Comments :

Sobre la Ley Antitabaco.

Creo que la Ley de No Fumar, va demasiado lejos.

Me parece que ya cayó en un "nivel neurótico" por parte de los no fumadores.

Reconozco y acepto el daño que provoca el fumar; pero también me queda claro que todo esto comenzó por el gasto que implica en salud para los gobiernos, el que la gente fume.

En estricto sentido surge de una cuestión económica y no, de un genuino interés por la salud de las personas. Si fuera así, también debería prohibirse el alcohol, los hornos de microondas, los antitranspirantes, las bolsas de plástico, los refrescos, los envases de plástico en todos los productos, todo lo transgénico, el glifosato, los pañales desechables, etc., etc., etc., etc., etc...Porque todo eso contamina la tierra y el agua y/o, nos enferma.

No estoy muy segura de que destinar espacios para fumadores en restaurantes, bares y hoteles, sea una buena decisión; porque la neurosis de los no fumadores y la incomodidad de los fumadores no son compatibles. Quizás sea mejor que existan restaurantes, bares y hoteles para no fumadores y restaurantes, bares y hoteles para fumadores. Y que cada quien decida a cual va.

¿Cómo se manejaría esto en los espacios públicos? Francamente no lo sé. ¿Alguien tiene una solución coherente para esto, que no pase por la imposición a unos y otros?

En lo personal, cuanto más me dicen que no se puede fumar, más ganas de fumar me dan. Esto surge de que viví y sufrí una dictadura militar y rechazo "visceralmente", todo tipo de imposición.

El tabaquismo es una adicción y debe tratarse como tal. No con métodos cohercitivos al estilo de La Inquisición. No puede educarse a través del terror. Y esto lo digo, por las imágenes espantosas que vienen en las cajetillas de cigarrillos, en donde vivo. Que además, no son todas ciertas.

¿No soy políticamente correcta? ¿Estoy transgrediendo la política de cacería de brujas que se está instaurando en todo el mundo, en muchos sentidos? No me importa en lo más mínimo. ¿Debería sentirme culpable por ser fumadora? No me siento culpable.

Los fumadores existimos y esa es una realidad.

Leticia Dino-Guida