“Nobody is born a democrat. Democracy is a social idea, not a natural occurrence, and citizens therefore have to learn about it.” That is the view of Professor Rolf Gollob, and he knows what he is talking about. Gollob is the national coordinator of the Council of Europe’s Education for democratic citizenship programme and works at the Zurich University of Teacher Education specialising in political education. He also knows that a wide range of programmes and initiatives already exist in relation to the topic. For example, the website www.politischebildung.ch contains a long list of institutions and official bodies in Switzerland and abroad that focus on it. There is nevertheless a lack of coordination and interconnectedness. “When it comes to political education, the left hand does not know what the right hand is doing,” remarks Rolf Gollob. Far too much energy is wasted.

The New Helvetic Society is now seeking to rectify the situation. To mark its 100th anniversary, the highly esteemed association is launching a campaign entitled “100 times political education”. “The importance of the issue is not in dispute,” remarks Hans Stöckli, President of the New Helvetic Society and a Council of States member for the Swiss Social Democratic Party (SP). “What is lacking is the political will to implement the promises made on the soapbox.” There is insufficient support for projects, he says, and Switzerland urgently needs a national centre of expertise for political education.

It is hoped that this focal issue, which looks to the future, will secure the New Helvetic Society’s own survival, as Hans Stöckli openly concedes (see interview). The society is fighting to change its image as an old gentlemen’s club and to counter a declining membership. It is now embarking upon a fresh start and has set itself ambitious targets.

Various initiatives concerning political education are to take place in the eight local groups. The New Helvetic Society is seeking to support, coordinate and raise the profile of projects of other organisations. It is planning to give young people the opportunity to attend national and cantonal votes and elections as electoral observers at key locations. “This will enable them to discover how democracy works at first hand,” explains Hans Stöckli. This part of the “100 times political education” programme is supported by the Swiss Cantonal Secretaries’ Conference.

Private funding required

The main element of the “100 times political education” programme is nevertheless the establishment of a national centre of expertise. “We will go from door to door to raise private funding for this,” says Hans Stöckli, “and we will canvas all the political parties for support and set up a cross-party lobby group for the project.” This should result in the creation of a national centre for political education with a broad-based trustee structure and a federal government mandate.

The need for this is highlighted by international comparative studies on the political knowledge and understanding of 15-year-olds. In 2003, Switzerland only finished in 19th position among 28 participating countries. The Swiss evaluation published at the time was entitled “Adolescents without politics”. The study organiser, Fritz Oser, complains of “political illiteracy” in schools, which he says is surprising in a “model democracy”. Three years later, a survey was conducted in Switzerland among 1,500 school pupils in Year 9. The results were sobering – virtually nobody was able to name the three powers at federal level correctly. And almost 70% thought that the Federal Council decided whether a referendum is accepted.

Lowering the voting age

The turnout among young adults at elections and referenda is also unsatisfactory: only just over 30% of 18 to 24-year-olds took part in the last national elections. The average turnout stood at just under 50%. “We must generate interest in politics among young people,” declared Federal Chancellor Corina Casanova at the New Helvetic Society anniversary event in Biel at the beginning of February. A political culture must be created where young people are included more. The Federal Chancellor sees a lowering of the voting age from 18 to 16 as a means of achieving this. This measure has already been introduced in Austria and several German federal states. “This would make it possible to close the gap between theory at school and practice at the ballot box,” explained Corina Casanova. A great deal of scepticism nevertheless exists in Switzerland. The canton of Glarus already has a voting age of 16, and the idea has been voted on in 18 cantons but rejected in all of them.

RETO WISSMANN is a freelance journalist. He lives in Biel

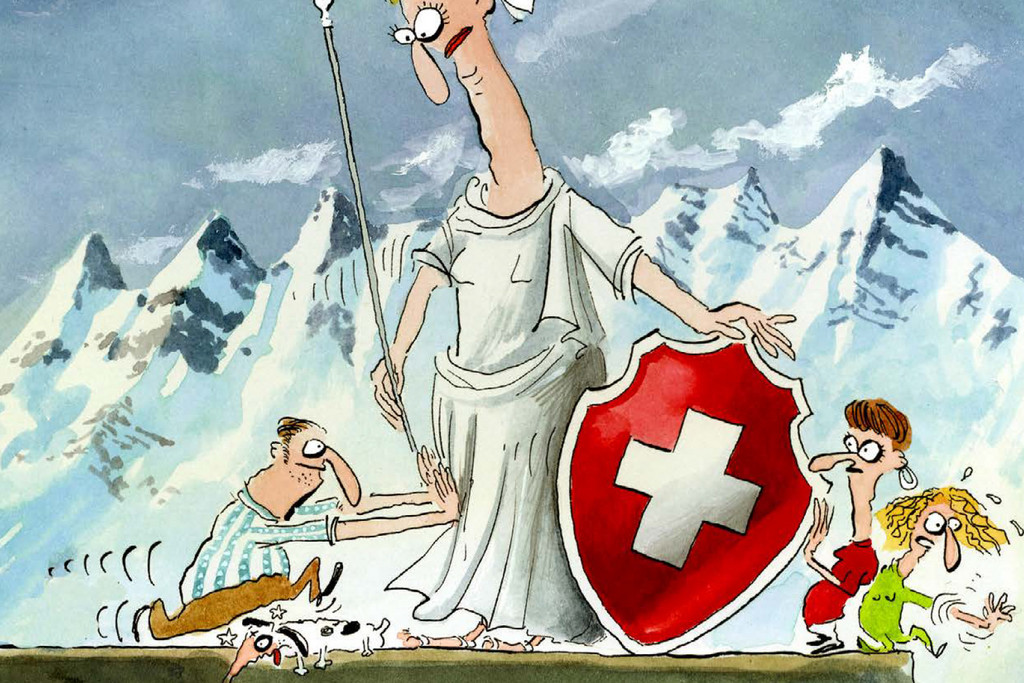

CUSTODIAN of national unity

The New Helvetic Society – a Meeting Place for Switzerland celebrated its centenary in Biel in February. However, the origins of the organisation go back much further. Back in 1762, proponents of different faiths came together to form the Helvetic Society in Schinznach Bad. Their goal was to turn Switzerland into a modern federal state.

Educated men from the middle classes and aristocracy worked on federal cooperation, religious tolerance and the development of a national identity in the most important pan-Switzerland association of the day. Its founders included the Basel town clerk Isaak Iselin, the Zurich doctor Hans Caspar Hirzel, the Lucerne councillor Joseph Anton Felix von Balthasar and the Bernese professor of law Daniel von Fellenberg. Ten years after it had achieved its objective with the signing of the federal constitution of 1848, the Helvetic Society was dissolved.

In February 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, literary figures, journalists and academics from French-speaking Switzerland as well as politicians and entrepreneurs from the German-speaking part drew upon the principles of the Helvetic Society and founded the New Helvetic Society in Berne. The driving forces included the Fribourg author and controversial admirer of authoritarian regimes Gonzague de Reynold as well as the Bernese writer Carl Albert Loosli.

The primary reason for its foundation was the threat to internal unity posed by the global political crisis. The organisation became well-known nationwide thanks to the “Unser Schweizer Standpunkt” (Our Swiss Standpoint) speech by Carl Spitteler, the poet and Nobel laureate for literature. Local groups soon emerged in various cities of Switzerland as well as in Paris, Berlin and London. Across party-political boundaries, the New Helvetic Society advocated multilingualism as well as the conservation of national heritage and of the unique characteristics of the respective parts of the country. The Organisation of the Swiss Abroad (OSA) was founded in 1916 thanks to the New Helvetic Society.

The society later supported Switzerland’s accession to the League of Nations, backed an initiative to preserve the Rhine Falls and contributed to the creation of the cultural foundation Pro Helvetia, the Stapferhaus museum at Lenzburg Castle and the ch Foundation for Federal Cooperation. Ideologically, the New Helvetic Society’s stance has fluctuated throughout the years mainly between a national conservative outlook and a policy of openness to the world. The New Helvetic Society had 2,540 members at its peak in 1920, while today there are still 850 in eight active local groups. In 2007, it merged with Rencontre Suisse, another civic association from French-speaking Switzerland. Its official title has since been the “New Helvetic Society – a Meeting Place for Switzerland”. www.politischebildung.ch

Source: Historical Dictionary of Switzerland

Comments