Switzerland is defined, among other things, by its commitment to conflict resolution, nuclear disarmament, and world peace. The Federal Council applied for a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council with these very goals in mind. Switzerland will remain at the high table of UN diplomacy alongside the world’s major powers until the end of 2025, debating political crises, sanctions and peace missions. Which is why signing the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) immediately would seem to be a no-brainer for the Federal Council. Switzerland was one of the 122 UN member states to negotiate and adopt the TPNW in 2017. But it is yet to ratify it.

The TPNW goes way beyond other existing treaties. It prohibits the production, possession, transfer, testing, use, and threat of use of nuclear weapons. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), meanwhile, is the cornerstone of today’s nuclear world order, defining the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, and China as nuclear-weapon states.

The new treaty is hard to swallow for Switzerland’s policymakers. On the one hand, the Federal Council believes that the TPNW fills a gap in international law, with nuclear weapons the only weapons of mass destruction never to have been subject to a comprehensive prohibition treaty until now – unlike biological and chemical weapons, for example. To ratify the TPNW would also be in keeping with Switzerland’s humanitarian tradition. And yet the same Federal Council has hit the brakes. After the TPNW was adopted, Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis said that the treaty was not the way to achieve these objectives. This has been the government’s view ever since.

Yet pressure is coming from parliament, which has already urged the government to sign the treaty on several occasions. Members of all the political parties have called for a nuclear ban, albeit for different reasons. The left-wing parties are committed to pacifist principles, whereas representatives of the SVP want ratification of the TPNW because this would make it harder for Switzerland to move closer to NATO – probably the very issue that explains why the Federal Council is stalling in the first place. Since the war in Ukraine began, the Western defence alliance NATO has taken on greater importance for Berne. By signalling its intention to join the Sky Shield air defence system (see Review 5/2023), the government has made its latest step towards NATO. Switzerland has been a NATO partner country under the Partnership for Peace programme since 1996.

But NATO also cooperates with countries like Austria that have already signed on the dotted line, say advocates of the treaty. Accession to the TPNW would not jeopardise Swiss security interests, in their opinion. Nevertheless, Western countries are exerting pressure on Switzerland to ditch the treaty for good. Once-neutral Sweden recently went through a similar process. NATO wants more in return for its friendship.

A federal government report published in 2018 already goes some way to allaying doubts, saying that Switzerland would probably cooperate with nuclear-weapon states or their allies, in the extreme case of self-defence against an armed attack. As a party to the TPNW, Switzerland would abandon the option of explicitly placing itself under a nuclear umbrella within the framework of such alliances. Commentators in Berne agree that Switzerland would be ill-advised from a foreign and security policy perspective to sign a treaty that not only questions the security doctrine of our most important partners but also attacks it directly by stigmatising nuclear weapons.

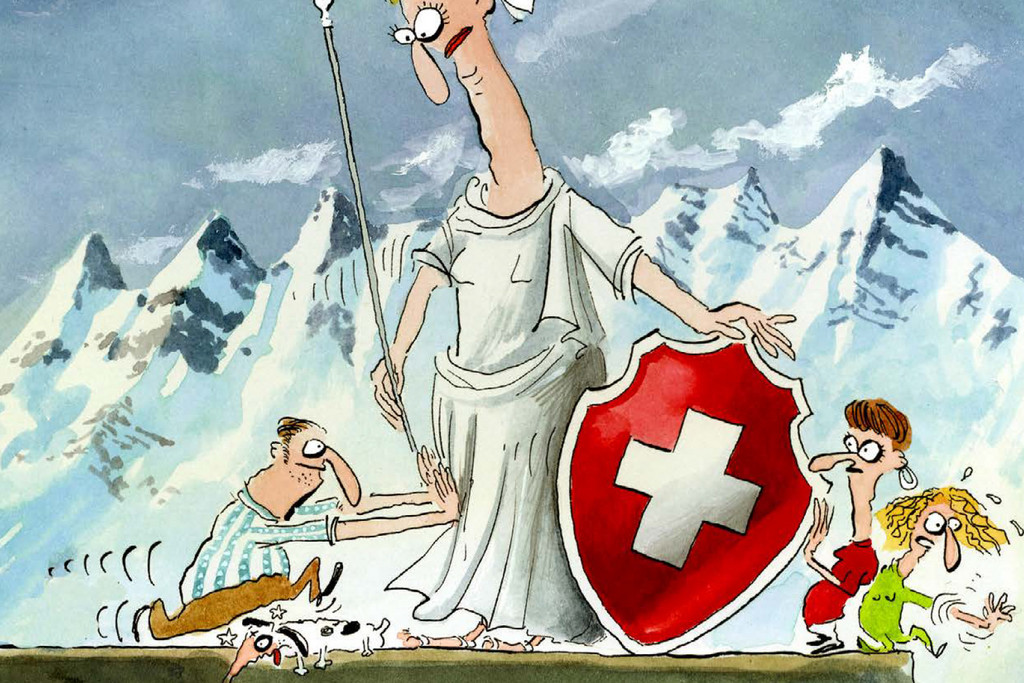

When Switzerland dreamt of the atomic bomb

From 1945 to 1988, Switzerland toyed with the idea of developing its own nuclear weapons. In a plan that was hatched only one month after the atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Federal Council and newly founded Study Commission on Atomic Energy (Studienkommission für Atomenergie, SKA) secretly worked on developing a “Swiss uranium bomb or other suitable means of war based on the principle of atomic energy” from 1946 onwards. The SKA managed to procure ten tonnes of uranium by 1955, of which half was stored as war reserve. In July 1958, the Federal Council issued the following declaration:

“In keeping with our centuries-old tradition of military defensiveness, the Federal Council holds the view that the armed forces must be provided with the most effective weapons in order to preserve our independence and protect our neutrality. This includes nuclear weapons.” Two popular initiatives opposing this view were rejected at the ballot box in 1962 and 1963. In spring 1964, a defence ministry working group in favour of nuclear testing in Switzerland (!) hatched a secret plan to procure an initial 50 atomic bombs followed by another 200 at a later date. It took years for attitudes to change. Berne signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1969, but it was not until 1988 that Switzerland’s secret nuclear weapons programme was officially shut down. (MUL)

Swiss National Museum blog post on Switzerland’s nuclear programme: revue.link/bomb

Relevant entry in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in German): revue.link/atombombe2

Comments