The Eritrean diaspora, the largest refugee group living in Switzerland, is under pressure. About 23,000 have been recognised as refugees; 9,500 are on temporary admission (F permit) and 3,000 are waiting for a decision. While the expulsion of the second group has been deemed impossible to implement, their files have been the subject of a re-examination since the summer. Holders of the F permit received a letter from the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM). “We are considering cancelling your provisional admission, which would result in your removal from Switzerland.”

Sent initially to about 200 people, the message plunged the diaspora into turmoil. “People, including those with a stable legal situation, such as a B or C permit, are worried that their situation will deteriorate,” says Tzeggai Tesfaldet, political opponent of the Eritrean regime and co-founder of two refugee associations in Geneva. “Teenagers have dropped out of school from fear,” says Aldo Brina, asylum officer at the Geneva Protestant Social Center (CSP).

The loss of the F permit will be brutal

The people concerned, if they do not appeal, will move from social assistance to emergency assistance, with an allowance of ten francs a day, and will have to leave their homes. “These people will be housed in the most dilapidated homes. This is the path to social disintegration,” predicts Aldo Brina. They will no longer have access to the labour market.

For this specialist on asylum issues, the policy is mainly aimed at diverting incoming Eritreans to other countries. “In Switzerland, people will not leave. Their situation will become precarious or they will go into hiding,” he predicts.

The recipients of the letter – a group that is growing - are invited to contact the SEM. The CSP reports that the Confederation has already gone back on several cases. “The pilot project showed that in 9 % of cases the cancellation of these admissions was proved to be proportionate and legally defensible,” says Emmanuelle Jaquet von Sury, spokesperson of the SEM. So far there have been about 20 cases of temporary admission being cancelled. Several appeal procedures are pending before the Federal Administrative Court (FAC). As for those seeing their F permits cancelled, they will be able to “return voluntarily to their country of origin without risk to their safety”, says the SEM.

National service and risk of rape

This change of policy towards the Eritreans has been carried out in several legal phases. The most recent was in July when the FAC made a decision relating to national service in Eritrea, made compulsory since the war with Ethiopia (1998–2000). Admittedly, the court is “convinced that ill-treatment does take place during military service… but it is not established that it is so widespread that anyone performing it would be exposed to the serious risk of suffering such attacks”.

The risk of rape for women conscripted by force is also not considered a sufficient criterion. “Sources do not allow us to conclude that every woman performing national service risks a sufficient probability of suffering such assault,” says the court. More generally, indefinite recruitment would not with sufficient certainty constitute forced labour, which international law condemns.

Radical change of course

In 2006, Switzerland decided to accommodate all deserters fleeing forced enlistment under the Eritrean flag, raising the rate of recognition of Eritrean asylum seekers from 6 % to 82 %. This period is over. “Eritreans are the largest group of asylum seekers in Switzerland, so there is immense political pressure to reduce their numbers,” says Peter Meier, spokesman for the Swiss Refugee Organisation. The Federal Department of Justice and Police is increasingly giving in to this pressure.”

“This policy is not linked to the fact that the refugees come from this particular country, or to the problems that this group poses, which are minimal, but to the number of people it constitutes,” says Tzeggai Tesfaldet. The social worker believes that “this deterrence is bearing fruit, since the arrivals are decreasing, although of course the closing of the Mediterranean route also plays an important role”. In addition, new asylum applications are now examined in the light of the new policy, reducing the chances of obtaining protection.

Defending the image of refugees

Two arguments, relayed by the media, may have weighed on the image of Eritreans in Switzerland. The first relates to the difficulty this group has in integrating. “Many Eritreans have only poor education… Most do not understand our writing and need literacy training,” says the SEM. An SEM study indicates that since 2002 all students have had to complete their secondary education at a military school, and only a limited number are allowed to study at one of the country’s higher education institutions. The others are forced to perform military service.

Another complaint is the fact that some refugees have returned to their country for holidays. “In 2017, the SEM withdrew refugee status from four Eritrean nationals who had made a visit to Eritrea. In the first half of 2018, the same applied to nine people,” says Emmanuelle Jaquet von Sury.

According to a report from the European Asylum Support Office, dated May 2105, exiled Eritreans apparently had the opportunity to enter the country to visit their families. To do this, or to obtain any official document, they must have paid a 2 % tax on income required by Eritrea from all members of the diaspora. “I do not pay this tax, which is used without any transparency and limits the rights of refugees,” says Tzeggai Tesfaldet.

Parliamentarians say good things

The perception of the authoritarian regime in Asmara may have been influenced by the visit in February 2016 of four parliamentarians. Interviewed on the spot by Radio Télévision Suisse RTS, the CVP National Councillor Claude Béglé, for his part, claimed that “Eritrea is opening up”. For Aldo Brina, this media operation has helped to change the perception of the public, yet the situation on the ground has not changed.

Are repatriated deserters at risk of abuse? “Since human rights observers cannot travel to Eritrea, and the International Committee of the Red Cross is not allowed to visit prisons, it is impossible to verify this,” says the European Asylum Support Office. As for the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, it was “obliged in 2006 to put an end to its commitment of several years in Eritrea in view of the difficulties encountered by local mutual assistance organisations”, according to the SEM.

A country being hollowed out

Every month, 5,000 people on average flee Eritrea, a country led by Isaias Afeworki and a single party. No elections have taken place and the constitution has never entered into force. The Eritrean community in Switzerland is estimated at 35,000 people. In 2015, about 25 % of European asylum applications were filed in Switzerland. The Eritrean diaspora totals almost half a million people, for a country of 5 million inhabitants.

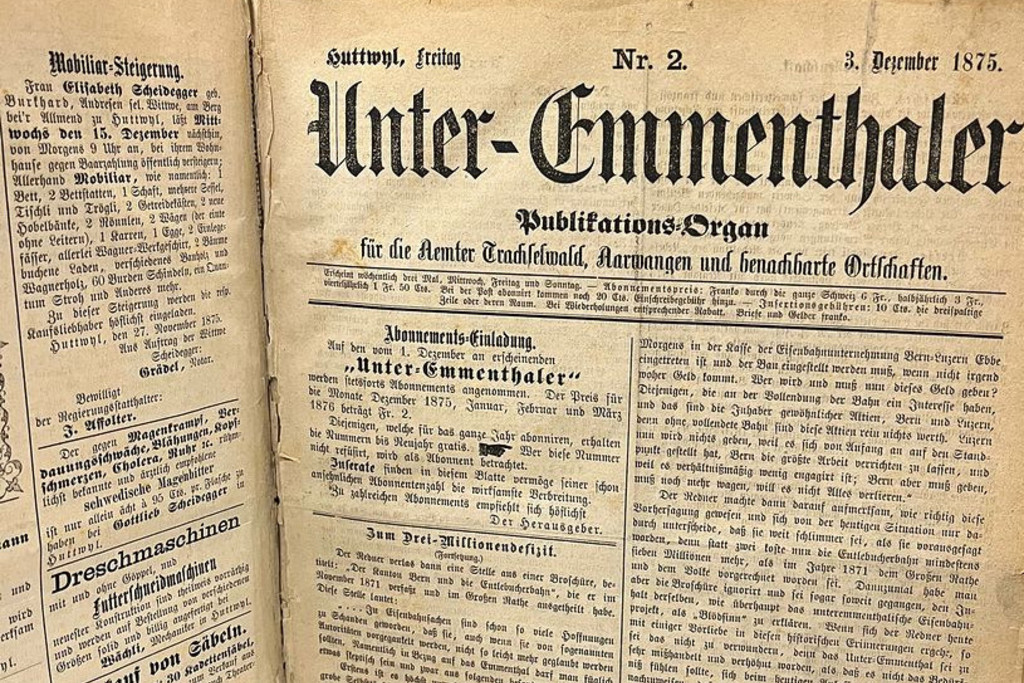

Picture: The Minister of Justice Simonetta Sommaruga surrounded by asylum seekers: Federal Bern is increasing pressure on refugees from Eritrea in particular. Photo: Keystone

Comments

Comments :

sont tous d'accord. La naivete de nos responsables est

effrayante. Ils doivent se poser la question de combien

de logements il faudra construire, vu que l'ONU prevoit

que l'Afrique aura une population de 5 milliards d'ici

la fin du siècle. Il vaudrait mieux leur apprendre le

planning familial en Afrique, souhaitable pour tout le monde.

Qu'est-ce qu'il avait dit Max Frisch ?

Bien cordialement,

Fakt ist: Afrika exportiert ihren unvernünftigen Geburtenüberschuss (Verdopplung der Bevölkerung alle 25 Jahre) nach Europa. Das wird nicht mehr lange gut gehen!

Es handelt sich erwiesenermassen grossmehrheitlich um Wirtschaftsmigranten und/oder Drückeberger vor dem Militärdienst.