- Society

Any teachers?

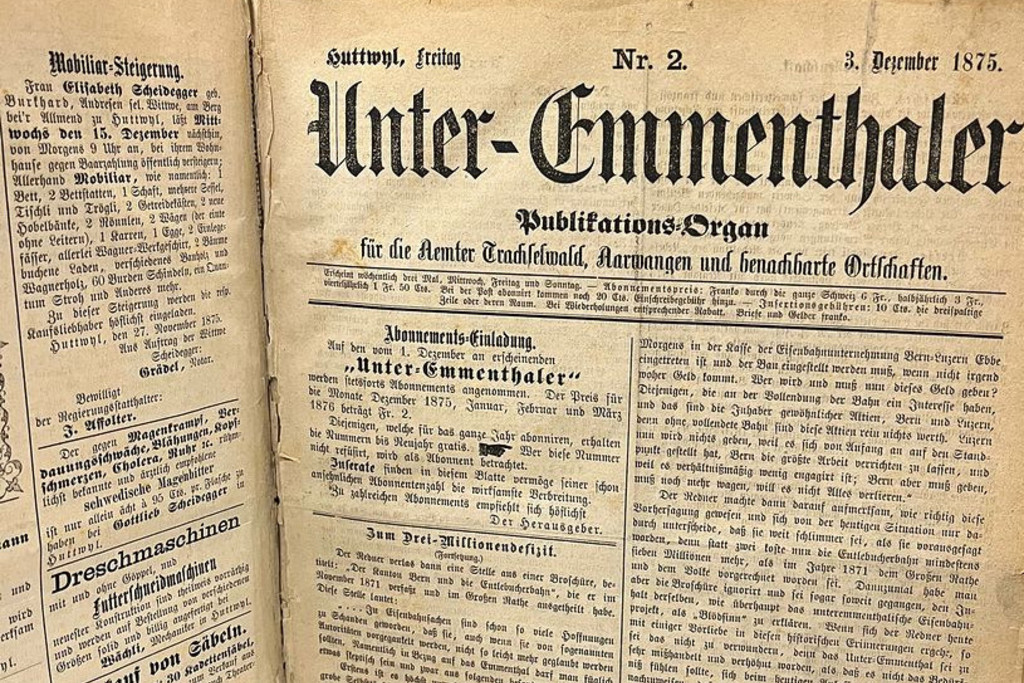

09.12.2022 – MIREILLE GUGGENBÜHLER

Although Switzerland’s state education system is generally well regarded, Swiss elementary schools are finding it increasingly hard to recruit trained teachers. Schule Schötz is one of them – but this particular school in the canton of Lucerne sees the teacher shortage as a chance to reinvent itself.

“We are good children and we try hard.” This is how one of the girls in Year 1 at Schötz elementary school (Schule Schötz) in the canton of Lucerne describes herself and her fellow classmates. She is speaking in a video that the head teacher uploaded to social media in spring 2021. The state school produced the clip in a desperate bid to find someone who could teach the children who had started school that year. The children themselves knew exactly the type of person they wanted. “Our teacher has to be good at football, kind, and not scold us.” At the end of 2022, the same children now have their dream teacher.

From globetrotting to teaching

Peter Bigler, the head teacher, is a happy man as he sits in his office. Some 100 people teach at his school. “Thanks to the video, we found someone who was travelling around the world when we interviewed them,” he says. Making the video was not something he had ever had to do before. Until recently, state schools in Switzerland have not had to worry too much about being able to recruit new staff.

A different kind of job interview: the kids of Year 1 talking on video link with their future teacher (who was still travelling around the world at the time). Photo provided by Schule Schötz.

Swiss elementary schools have a good reputation – 95 per cent of all the country’s pupils attend state school while the remaining five per cent go to private school. Confidence in state schools is high compared to that in other countries. Domestic commentators often refer to education as Switzerland’s ‘most important’ or ‘sole’ resource. It used to be relatively easy for schools to find qualified teachers, but this has changed over the last two years. Few, if any, people are now applying for teaching vacancies. This is down to various factors. For example, more teachers are retiring than lining up to enter the classroom. According to the federal government, pupil numbers have also been steadily increasing since 2016, and will continue rising until 2031. A lack of qualified people on the market, coupled with burgeoning class sizes, has left state schools with staffing problems. Another phenomenon exacerbating the situation: most teachers in Switzerland – especially at primary school level – are women who work part-time. This means schools need teachers in greater numbers to meet their pupils’ full-time needs.

Teacher shortages are particularly acute in German-speaking Switzerland. The situation is a little less dramatic in French- and Italian-speaking Switzerland.

Teachers without teacher training

Even Switzerland’s most senior head teacher Thomas Minder, who chairs the Swiss head teachers’ association, has to pull out all the stops to fill vacancies with suitable staff at his own school. More and more people with no teacher training or with no certificate for the level at which they want to teach are applying for jobs. Head teachers end up hiring these applicants, because there is no other option. “I once approached someone I know in a private capacity, because I think this person is good at dealing with children and we simply couldn’t find anyone else,” says Minder. But nothing came of it in the end, and he was able to recruit someone qualified after all. Minder: “One or two without teacher training in each team is fine. But no more. And my staff have to be satisfied that the teaching doesn’t suffer as a result.”

975,000 children go to school in Switzerland (from nursery school age to 15 years old). Over 11,600 schools make this possible. The reputation of Swiss primary schools is very good: 95% of all children go to state school.

It is unclear how many people in Switzerland teach without having done teacher training. The Federal Statistical Office only gives a full-time-equivalent (FTE) figure for total staff without full qualifications. In the canton of Berne, for example, the number of teachers without full qualifications in the 2020/21 school year amounted to about 1,038 FTEs. The number of equivalent FTEs in the canton of Zurich was 782.

Exodus to other professions

“We won’t solve the problem of teacher shortages in the short term,” says Minder, who believes that action is also necessary in areas where change will likely take longer. “Too many teachers are moving to other professions. We need to make it easier for them to return to the teaching profession.” Furthermore, many erstwhile student teachers get cold feet after they start work. “This is why it is imperative that people do aptitude tests before getting into teaching training.”

Photo provided by Schule Schötz.

A novel approach

Schötz elementary school also had to go looking for new teachers for the new school year. Not an easy task. But Peter Bigler was able to fill all 20 vacancies. Did he shoot another video? “We are indeed still producing videos,” he laughs. “But now the videos give insights into how we work.” The school has sharpened its profile in order to stand out from its peers – something you normally only see in Switzerland’s private education sector. “Private schools are a little bit ahead of us in that regard,” he says.

Bigler again: “In our teaching, we focus increasingly on promoting four general life skills: collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking – because we believe these qualities are of particular value in the 21st century.” The school has created its own dedicated teaching modules, including an Inventors’ Workshop. As far as Bigler is concerned, the current teacher shortage is not a crisis. “On the contrary, it is a chance for us to shape and not just manage school life. To follow a vision and break with orthodoxy.”

Comments