At the age of 91, Heinrich Oswald voluntarily ended his life with the help of the assisted suicide organisation Exit at home in the canton of Zurich and in the presence of his two sons. He had become increasingly frail in the year before his suicide. He still lived in his own home, but had suffered two serious falls, required care and the doctor had told him that he could not carry on living without a urinary catheter. “The second fall made up my father’s mind that enough was enough,” says Ueli Oswald, one of his sons. His father - a well-known company director and army reformer - greatly feared becoming dependent upon people. In 2009, Ueli Oswald wrote a book about the suicide of his elderly father. He had always emphasised that he was not tired of life but rather “had lived long enough”.

It was a question of going when he had had enough. Switzerland’s largest assisted suicide organisation, Exit Deutsche Schweiz, wants to facilitate such rational suicides. This spring, the general assembly accepted an amendment to the articles of association with the aim of assisting suicide in old age. Previously, Exit primarily provided assisted suicide for people with incurable, chronic illnesses, most commonly cancer. This requires a doctor’s prescription for the lethal drug, a barbiturate.

However, one in five assisted suicides at Exit does not concern the terminally ill but instead elderly people with numerous age-related complaints. They no longer see and hear well, are in pain, are incontinent, are no longer mobile and are exhausted. Elderly people who wish to die should in future be given “facilitated access” to means of dying. Self-determination is a human right “until the last”, writes a group of elderly Exit campaigners who are extremely committed.

Not begging for a “dignified death”

“The initiative for assisted suicide in old age comes from the Swiss people,” remarks Bernhard Sutter, Vice-President and spokesperson for Exit. Many elderly people do not believe it is right that a 90-year-old should have to plead for a “dignified death”. Exit does not say how exactly the threshold should be lowered: “That must be regulated by the legislator.” Nor does Exit specify the age from which facilitated suicide should apply: “How someone feels in old age is specific to the individual,” points out the Vice-President. There are fit 90-year-olds and 80-year-olds with already very restrictive illnesses. Dying cannot be governed by rigid categories: “Only those concerned can decide for themselves based on their subjective perceptions.”

Switzerland has a liberal policy towards assisted suicide. It has been permitted for over 60 years as long as the assistance is not for self-serving reasons. Criticism has been and still is voiced by religious and medical groups who point to the possibility of pain-relieving, palliative care. There is nonetheless a broad consensus that it should be possible to take one’s own life in a humane way in the event of unbearable suffering. In 2011, the Federal Council rejected its original plans to restrict or even prohibit organised assisted suicide. It said the applicable law was sufficient to combat any abuse. However, the debate has now been relaunched with an eye on assisted suicide for the elderly. The easing of regulations that Exit is aiming to secure is likely to require legal amendments. Cautionary voices at Exit therefore fear that the campaign will ultimately not result in further liberalisation but, on the contrary, lead to more restrictive regulation of assisted suicide.

“Problematic signal”

Doctors face a critical test. According to their professional standards, they can only administer lethal drugs to patients in the last stage of a serious illness. “Exit is now pursuing a path whereby any kind of world-weariness and wish to die would justify medical assistance with suicide. I am sceptical about that,” says the Zurich-based geriatrician Daniel Grob in an interview with the “Tages-Anzeiger”. Instead of just pulling out the prescription pad for lethal drugs, the approach should be to listen to exactly what lies behind the elderly person’s wish to die. Various geriatricians point out that it could be a manifestation of depression. Those around the person then wrongly attribute social withdrawal and lethargy to old age. But if the depression were treated, the person concerned could recover, they say.

Gerontologist and theologian Heinz Rüegger from the Diakoniewerk Neumünster – Schweizerische Pflegerinnenschule foundation, which runs a hospital and several care homes in the canton of Zurich, fears adverse social consequences. Rüegger, himself a member of Exit, actually supports the right of individuals to end their life. “Facilitating suicide for the elderly could, however, put subtle pressure on the older generation not to become a burden to anyone,” says the ethics expert. The need for care is already primarily perceived as a cost factor. And people fear losing their autonomy in old age and suffering from dementia. Old age has negative connotations. In this climate, Exit is sending out “a problematic signal”, according to Rüegger.

A “long-life” society

The Swiss population is becoming increasingly aged. Statisticians are predicting a particularly sharp rise among the over-80s. In this “long-life society” a different ageing culture is required in Rüegger’s view. “Being often dependent upon others is part of life.” That is not insulting but normal. Enjoying life to the full until there is no more left and then deciding for oneself to voluntarily end one’s own life in a clinical way – this positive image painted by some advocates of suicide in old age does not convince the academic. Suicide here becomes “almost the final part of a wellness treatment”. Rüegger believes that dying in a different way is also a dignified death. Trials, tribulations and debilitating experiences should be incorporated into life plans once more, he thinks.

The question is whether Exit cultivates fear of ageing. Are the elderly being put under pressure to end their own lives in due time and in a socially acceptable way? Vice-President Bernhard Sutter counters: “A 90-year-old long-suffering patient does not fear old age, he has been old for years. But he wants to end his suffering which could go on for months or years.” Exit is not planning to extend assisted suicide or to change the criteria for it: “It is about someone who is very elderly having to provide less justification, for example, to a doctor than a 65-year-old does.” Careful checks will continue to be made to determine whether the person wishing to die is under any pressure. If this turns out to be the case, assistance from Exit will be out of the question because the party assisting the suicide would then become liable to prosecution.

The risks of extending the grounds for assisted suicide should be taken seriously, according to the author Ueli Oswald, whose father voluntarily ended his life with Exit. However, the decision must ultimately lie with the individual: “Death was what my father wanted in his heart.” The family shared his last moments and were able to say goodbye. This would have been different if his father had secretly planned to throw himself in front of a train or to shoot himself: “But this way he went peacefully. I could see that.”

Susanne Wenger is a freelance journalist. She lives in Berne.

Assisted suicide in Switzerland

There are several assisted suicide organisations in Switzerland. With around 75,000 members, Exit Deutsche Schweiz is the largest. It restricts its activity to persons residing in Switzerland or with Swiss citizenship. In rare cases, Exit provides assisted suicide for Swiss citizens abroad, as spokesperson Bernhard Sutter explains. These are primarily Exit members who have emigrated after retirement and suddenly fall ill with cancer. In 2013, Exit Deutsche Schweiz carried out 459 assisted suicides. In 2012 the number was 356. Every case is investigated by the police and the office of the public prosecutor. In contrast to Exit, the Swiss organisation Dignitas also provides assisted suicide for foreigners wishing to die. According to a study by the University of Zurich, suicide tourism is growing in Switzerland.

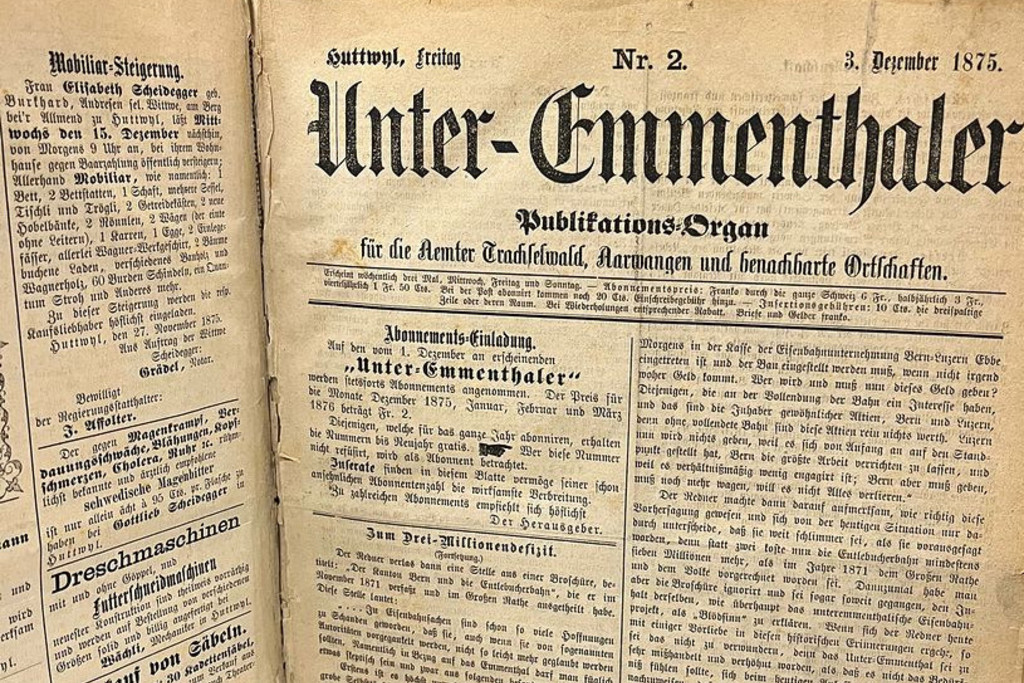

Picture My will be done! Elderly people are increasingly adopting this attitude when it comes to death

Comments

Comments :

I'm Lucky that I am Swiss.

Aus Ignoranz sieht eine Mehrheit der Menschen den Tod als Feind an, anstatt ihn als den lebensbegleitenden Freund zu achten der uns zu sich holt wenn unsere Zeit hier abgelaufen ist. Leben und Tod sind ein dualistisches Paar und deshalb unzertrennlich. Wir kaufen dieses Los mit dem Leben selbst. Aber da ja das Leben selbst endlich ist, kann auch der Tod nicht ewig sein. Das Thema der Wiedergeburt ist ja auch deshalb immer aktuell und bei genauerer Analyse die einzig fernünftige Antwort auf die vielen unbeantworteten Fragen die das Leben und den Tod betreffen.

Für mich ist es absolut unverständlich, dass ein Mensch in einer liberalen, säkularen Gesellschaft um seinen eigenen Tod betteln muss. Pflegebedürftigen geht es meistens nicht so sehr darum, anderen nicht zur Last zu fallen. Mancher alte Mensch, der sein Leben lang gearbeitet hat, könnte leicht für sich in Anspruch nehmen, sich nun von anderen umsorgen und pflegen zu lassen und somit anderen zur Last zu fallen. Es geht doch vorab darum, dass diese Menschen nicht mehr s i c h s e l b e r zur Last fallen wollen.

Ich fände es auch angebracht die Terminologie zu präzisieren. Suizid, Selbstmord ist ein Schritt aus Verzweiflung, der auch bei Hinterbliebenen Verzweiflung und Schuldgefühle zurücklässt. (Ich weiss aus bitterer Erfahrung wovon ich rede.) Freitod ist ein stolzer, autonomer Schritt, den zu tun ein jeder das Recht haben müsste. Sollte ich einmal in der Situation sein, diesen Schritt tun wollen, möchte ich mich nicht Ärzten, Richtern und schon gar nicht von Pfaffen daran hindern lassen. Alle diese wohlmeinenden Leute können und wollen nicht verstehen, dass das höchste Rechtsgut, der Schutz des Lebens, sich für Menschen in bestimmten Lebenslagen gegen sie richtet.

Luckily I have Swiss Citizenship and was able to join

Exit as a member. It gives me great consolation to know

that I can chose my quality of live in my old age. Most of

old poeple live in plain misery. The impotance is that this is discussed with your family and your doctor. Unfortunaltely religion tries to interfere in poeples life and death decisions. I'm proud that most Suisse

poeple are broad sighted.

Darum reden wir auch miteinander, lassen uns beraten, geben vertrauten Menschen die Möglichkeit uns zu beeinflussen. Wir wollen den Input derer, die uns lieben.

Aber am Schluss treffen wir die Entscheidung, was wir machen wollen selber.

Der Staat gibt mir diese Freiheiten, solange ich meinen Mitmenschen nicht schade.

Ich bin frei zu wohnen, wo ich will, die Karriere zu verfolgen, die ich will, den Lebenspartner zu wählen, den ich will, etc.

Warum habe ich diese Freiheit vom Staat nicht, wenn es um MEIN Leben geht?

Natürlich braucht der Staat eine Verwaltung obiger Freiheiten; darum gehen wir auch aufs Einwohneramt, wenn wir umziehen wollen und füllen einige Formulare aus.

Das wesentliche dabei ist, dass der Staat mir keine Hindernisse in den Weg legt, die es schwierig machen an einen andern Ort umzuziehen.

Warum kann ich nicht aufs Einwohneramt gehen und sagen: "Ich möchte umziehen. - Diesmal aber ganz weg von dieser Welt. Können Sie mir zeigen welche Formulare ich ausfüllen muss, damit ich das in die Wege leiten kann?

Danke."

Steuergesetze in der Schweiz gegenueber alten Leuten, sind

unmeschlich. Die alten Leute, die sich waehrend der Arbeitsphase eine Wohnung, oder ein Haus erspart haben, koennen die Eigenmietwert- Steuer ohne regelmaessiges Einkommen nicht mehr bezahlen.Wenn dann die Ersparnisse zu ende gehen, bleibt, um der Erniedrigung aus dem Weg zu gehen, nur suicide.

Niemand wird zu irgend etwas gezwungen, auch nicht ein begleitender Arzt. Hingegen werden alte Menschen zunehmend bevormundet, gerade auch von der Gesundheits- und Altersindustrie. Das kann bis zur Entwürdigung gehen. Wer sich dem entziehen möchte, braucht Unterstützung, von Vertrauenspersonen regelmässig, und vielleicht dann auch einmal von einer Sterbehilfeorganisation. Diese konkrete Unterstützung sind wir diesen Menschen schuldig, aus Liebe, Respekt und Menschlichkeit. Dem gegenüber haben abstrakte gesellschaftspolitische Vorstellungen zurückzutreten.