The day the “Fifth Switzerland” became official

Thomas Strässle | Beyond the border

Martin R. Dean | Trinidad and Aargau

Michel Layaz | Chevrolet: The man behind the wheel

Alexandre Lecoultre | A tale of two languages

Pasqualina Perrig-Chiello | Growing older means redefining yourself

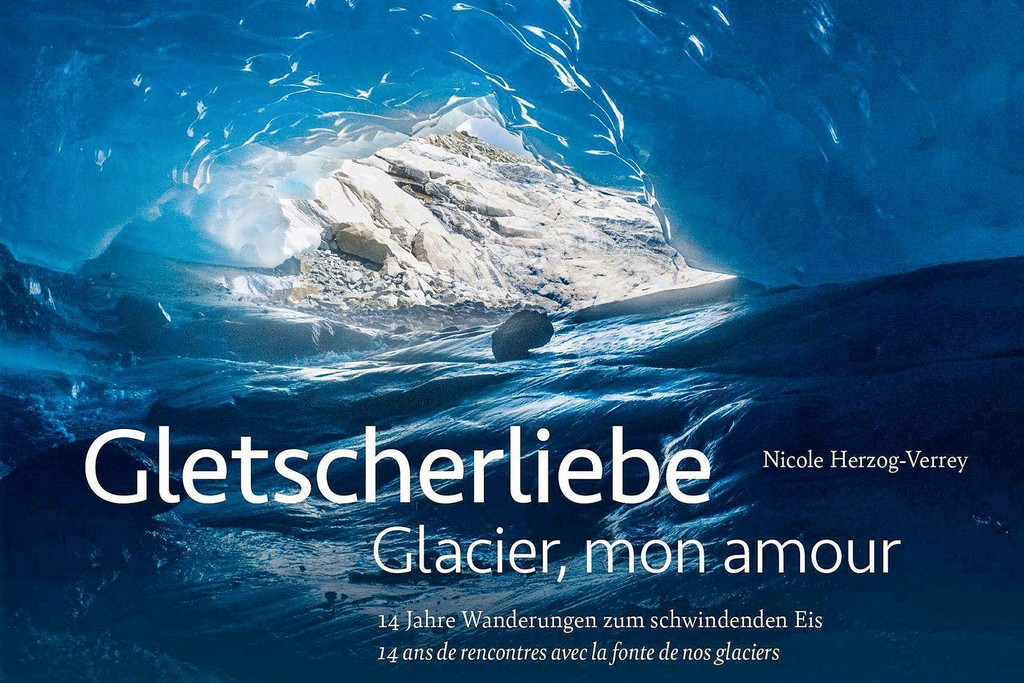

Nicole Herzog-Verrey | Declaration of love for the threatened Alpine glaciers

Comments